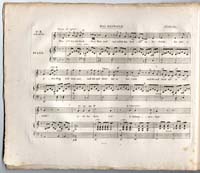

Zwoelf Gesaenge

Op. 8

(Berlin: Schlesinger [1826–1827])

Includes songs by Fanny (uncredited) as well as by Felix

A famous and well-connected prodigy, Mendelssohn began publishing his music in 1823, at the tender age of fourteen. By the time Schlesinger issued the songs displayed herein two installments, in 1826 and 1827Mendelssohn had already reached Opus 8. This set of twelve songs includes only nine by Mendelssohn. The other three (including Italien, shown here) are actually by his older sister Fanny (18051847), although her name appears nowhere. This peculiar arrangement was repeated in Felixs Op. 9 songs; again, three out of twelve were composed by Fanny, but without credit.

In 1842, Felix visited Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace. He happened to notice the Zwoelf Gesaenge on the Queens piano, so he invited her to sing for him. She chose Italien, and according to Felixs letter to his mother, she performed it well, though she did sing two wrong notes. (Despite her royal status, he did not hesitate to correct her.) After she had finished, he swallowed his pride and explained that Fanny was actually the composer of this song, and he asked the Queen to sing something else that was truly his own work.

By all accounts, Fanny Mendelssohn (later Fanny Hensel) was an extraordinary musician. Like her brother, she benefited from both natural talent and rigorous training, and became an outstanding composer, pianist, and conductor. Unlike her brother, she was not allowed to pursue a career as a professional musician, because her family believed that it would be inappropriate for a woman, especially one of her social standing. She could compose, and she could perform in ostensibly private musical gatherings at the Mendelssohn home (which in fact attracted large audiences, and became a major part of the music scene in Berlin), but she was not permitted to appear on stage, accept money for her work, or let her name be published as a composer. This was the edict of her father, Abraham Mendelssohn, and Felix supported it, despite his exceptionally close personal and musical relationship with his sister. Not until 1846 (more than a decade after Abrahams death) did Fanny finally begin to publish under her own name, with the enthusiastic support of her husband and the cautious acquiescence of her brother. Unfortunately, she died only a few months later.