Back to Liszt Exhibit Home | Exhibit Gallery

Franz Liszt

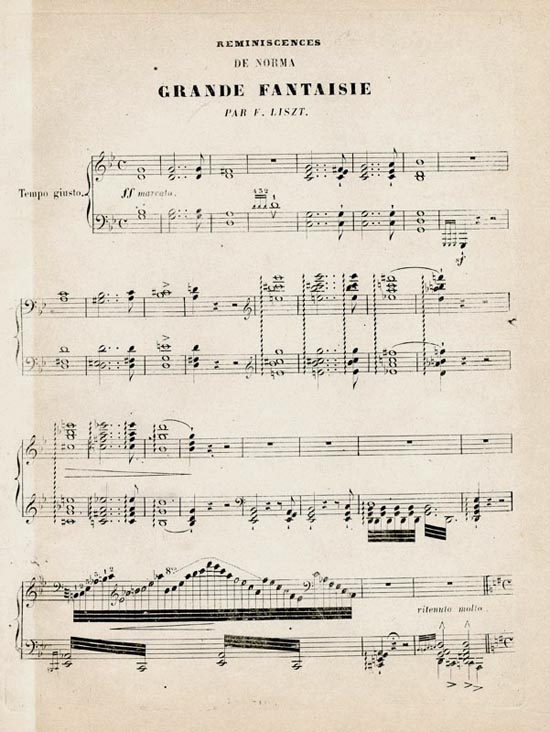

Réminiscences de Norma: Grande Fantaisie

(Mainz: Schott, [1844])

From the library of Vladimir Horowitz

Gilmore Music Library

To Previous Exhibit Item | To Next Exhibit Item

Liszt’s transcriptions fall into various categories. Some are fairly straightforward piano arrangements of orchestral works such as Beethoven’s symphonies or Berlioz’s Symphonie fantastique. Arrangements like these played an important role in the musical culture of the nineteenth century; they were the principal way many music lovers came to know operas and orchestral works. (Not everyone had the opportunity to attend live performances, and sound recording technology had not yet been invented.) The creation of arrangements like this was sometimes regarded as hack work, but Liszt took it very seriously, and he was renowned for his ability to simulate orchestral effects on the piano. In a similar vein, Liszt wrote piano transcriptions of music for voice and piano, such as Schubert’s songs. These usually retain the character of the original song and the composer’s interpretation of the vocal text, even though the words are no longer present.

Finally, Liszt produced more flamboyantly virtuosic pieces (which he called “paraphrases”) that are not direct transcriptions at all, but rather free compositions based on themes by other composers, typically from operas. Fantasies of this kind were a staple of the repertory of most touring virtuosos, although many of them remained unpublished (and thus unavailable to the competition). Liszt’s Reminiscences de Norma (which borrows its raw material from Vincenzo Bellini’s opera) is an example of this genre.

This score is one of several items on display that came to Yale from Vladimir Horowitz, who admired Liszt greatly and performed his music frequently and with great success. In some ways, Horowitz (1903–1989) was Liszt’s closest counterpart in the 20th century. Although Horowitz ultimately chose to concentrate exclusively on the piano rather than pursue his childhood dream of becoming a great composer, his astonishing fantasies on Bizet’s Carmen and Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever are rare twentieth-century examples of a tradition that had nearly become extinct.